How many times has your organization moved in a direction you disagreed with?

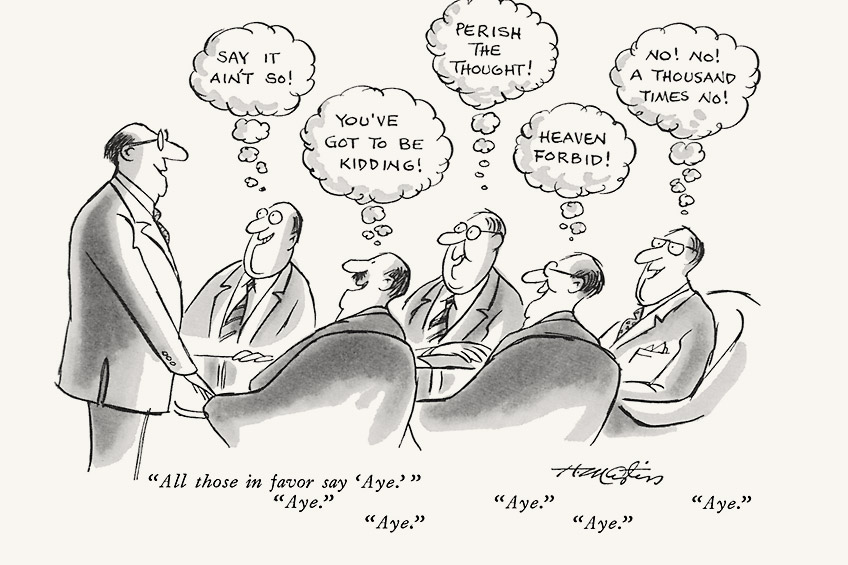

Have you found yourself saying ‘yes’ to a group decision or project when you really meant ‘no’?

How many seemingly well-supported decisions ended up being wrong turns that cost time and money?

Each of these scenarios might signal an unplanned trip to Abilene. There are times when leaders do not recognize that their teams are on the road to Abilene. The telltale signs are, “we all get along” or “we go with the flow”.

The term Abilene Paradox was first noted by management professor Jerry B. Harvey in his 1974 paper The Abilene Paradox: The Management of Agreement. Harvey uses the following anecdote to illustrate the paradox.

On a summer afternoon in Coleman, Texas, a family is visiting, playing dominoes on the porch and trying to stay cool. The father-in-law suggests a drive to Abilene to eat dinner in the cafeteria. The others have doubts but agree to the trip. They drive to Abilene in sweltering heat, along rough country roads, to have a not-so-great dinner. Returning home exhausted, each family member shared their true feelings: none of them wanted to go to Abilene in the first place. They only agreed because they thought the others wanted to go. If only someone had spoken up, the miserable journey could have been avoided.

After the episode in Coleman, Harvey observed that the paradox can be seen in various groups that attempt to reach an agreement while solving a problem. Paradoxically, the agreement they reach is contrary to the expected outcome. Harvey writes, “Organizations frequently take actions in contradiction to what they really want to do and therefore defeat the very purposes they are trying to achieve.”

While the family in the example above experienced only a minor inconvenience, the Abilene paradox can have devastating real-world consequences. Dr. Harvey cites the Watergate scandal as an example. Those involved in the break-in and subsequent cover up had their reservations, but decided to suppress them, as dissent could potentially cost them their jobs or invite ostracism. When interviewed individually, the participants revealed that they had personal qualms but did not want to risk being labeled as traitors and wanted to be seen as “team players.”

Whether in social situations or organizations, going along to get along arises from a desire to avoid conflict and a reluctance to be seen a “spoiler” who criticizes ideas or plans that appear to have widespread support. The choice to speak up and risk censure or go along to please the group produces discomfort and could involve risk – to relationships, career, or both.

It may seem that group members are in conflict, but the problem is not conflict and its management, according to Harvey. Rather, the problem is the management of agreement.

Against the backdrop of new working policy rollouts, individual health concerns, and changing attitudes toward work post-pandemic, leaders will need to manage agreements today more than ever in order to retain talent and bolster team performance.

It is easy for leaders to assume they know what their teams want when they return to the office.

False consensus causes leaders to think their team members share their beliefs, which is often not the case. When leaders go into auto-pilot mode and simply assume, they run the risk of violating trust and communicating poorly.

Surveys and research have shown that habits, norms, and values developed during the pandemic will continue to have a significant impact on the post-COVID workplace. According to a Bloomberg survey, 39% of respondents said they would consider quitting if their employers weren’t flexible about remote work. In what’s been termed the “Great Resignation,” 95% of workers are now considering changing jobs, and 92% are willing to switch industries to find the right position, according to a recent report by Monster.com.

Leadership and teamwork can be thought of as analogous to an iceberg. The 90% of the iceberg hidden below the waterline is what creates the behavior seen by the 10% that is visible at the surface. Asking “why” and getting “below the iceberg” to understand people’s beliefs and motivations can help leaders defend against mental blind spots and make the best strategic decisions for their teams.

Here are some steps leaders can take to get underneath the surface:

Prioritize feedback. Some leaders might not be aware of how they surround themselves with yes-people or that the power of their personalities might silence others. TINYpulse (www.tinypulse.com) is a software tool that collects continuous, anonymous employee feedback in real time, offering everyone an opportunity to speak up without fear of consequences.

Hold regular one-on-ones: While it can seem like time and attention are scarce, deep listening pays long-term dividends by helping to reduce burnout, decrease turnover, and optimize productivity. Leaders should: create a safe environment where people are free to voice their concerns and opinions, no matter how unpopular; be proactive in having conversations rather than waiting for problems to arise; and consider delegating – team members might be more comfortable sharing input and reactions with their colleagues or direct managers.

Gather outside information and perspectives: This could be an optimal time to invest in your organization by getting some targeted suggestions in order to regroup, refocus, and reengage. Our staff supports leaders and teams with education, processes, and practice to improve effectiveness, communication, and accountability. Using a team’s real business issues and assessment tools such as the Group Development Questionnaire (GDQ) our approach provides research-backed insight into your team’s current stage of development and actionable steps to improve team effectiveness in an altered world of work.

We invite you to share your experiences with taking or getting off the road to Abilene in the Comments.

If you find that your organization is continually making the trip, please contact us at info@thepropel.com.

References:

“Explanation of the Abilene Paradox with Examples.” PsycholoGenie, psychologenie.com/explanation-of-abilene-paradox-with-examples.

Harvey, J. B. (1974). “The Abilene Paradox: The Management of Agreement.” Organizational Dynamics. 17-43.

Leave A Comment